Headwaters was the last old growth redwood forest to be saved.

Ours was the first to be lost.

by Russell Yee, 1997

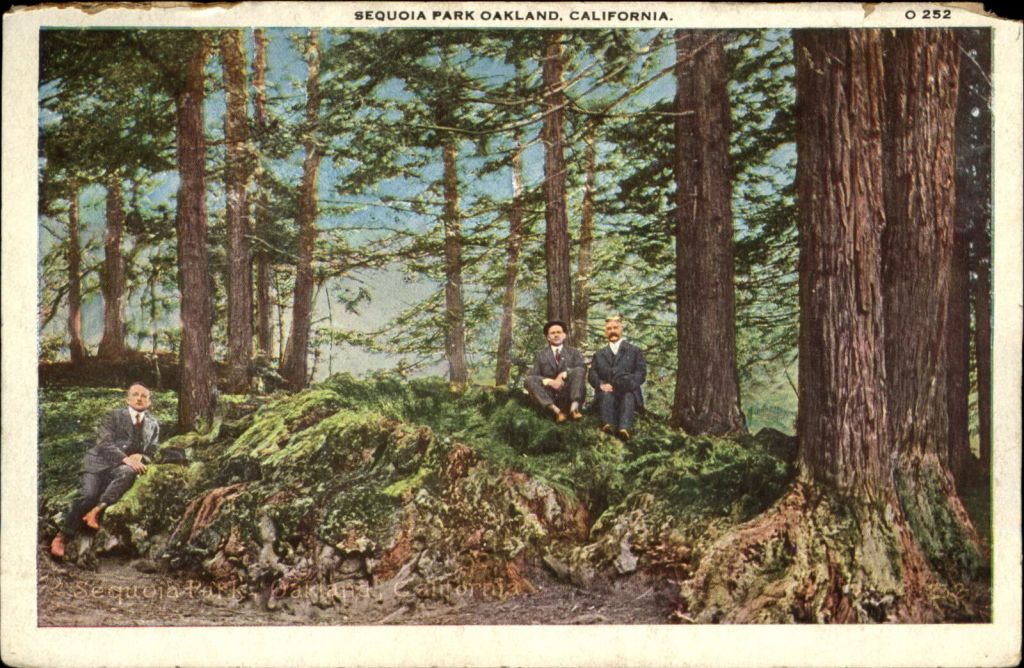

Five miles and fifteen minutes from downtown Oakland, I’m standing alone in a redwood forest, about halfway up a steep hillside. The only sounds I hear are the chatter of birds, the wind in the trees, and a creek splashing far below. The canopy of branches high above bathes everything around me in dappled shade. It rained yesterday, so the forest floor is glistening, and fresh. At first glance, other than the trail I’m on, nothing I see–the trees, the huckleberry bushes, the wild ginger and sword ferns–tells me humans have been here in consequence. For the moment at least, there’s not even the sound or sight of a mountain bike to tell me roughly what century it is. But then I notice that all the redwoods are unnaturally uniform in age, all fairly young for the species, maybe a century old or less, and crowded in clumps. Someone has been here. Something happened.

And the Lord God made all kinds of trees grow out of the ground . . . . In the middle of the garden were the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

Genesis

Before the 19th century, about 2-million acres of virgin coast redwoods stood in California, the equivalent of about four times the area of Alameda County. These trees stood in six major “islands,” all within reach of the coastal fogs. The most southerly “island” was a thin archipelago along the Santa Lucia range from above San Simeon almost up to Monterey, where relatively small, scattered redwoods grow in isolated deep streambeds. The next “island” north was the much wider belt starting from above Watsonville, overspreading the Santa Cruz mountains, and up the Peninsula. This second “island: includes Big Basin, established in 1902 as the very first California State Park.

Across the Golden Gate was the third “island,” from the slopes of Mt. Tamalpais almost to the top of Marin County, but not including our visiting chunk of southland, Point Reyes. This third “island” includes the most heavily-visited stand of virgin redwoods by far: Muir Woods National Monument, personally saved in 1907 by Congressman William Kent from flooding as a reservoir. This “island” also includes numerous small “islets” to the east, all the way into Napa county.

Continuing north, the fourth and fifth “islands” make up the Redwood Empire, each larger than all the other “islands” combined. The fourth was the great belt from the Russian River to the Lost Coast, where Highway 1 heads inland. Much of it is no longer even forested, having been logged and cleared for pastures, farmland, and vineyards. Some beautiful but small virgin stands remain in a handful of State Parks and Reserves, mostly along Highway 128.

The fifth and greatest belt is from the bottom of Humbolt County up to just over the border with Oregon, which now includes Humbolt Redwoods State Park (containing the largest intact stand of virgin trees: the 9,000-acre Rockerfeller Forest, endowed by John D. Jr.), Redwood National Park (containing several of the world’s tallest known trees), and the now-famous Headwaters Forest (containing the last large stand of virgin trees to have been in private hands). There the abundant rainfall but still moderate temperatures combine to produce redwoods in their greatest glory, with many large, pure stands, and many specimens in the finest groves exceeding 300 feet tall.

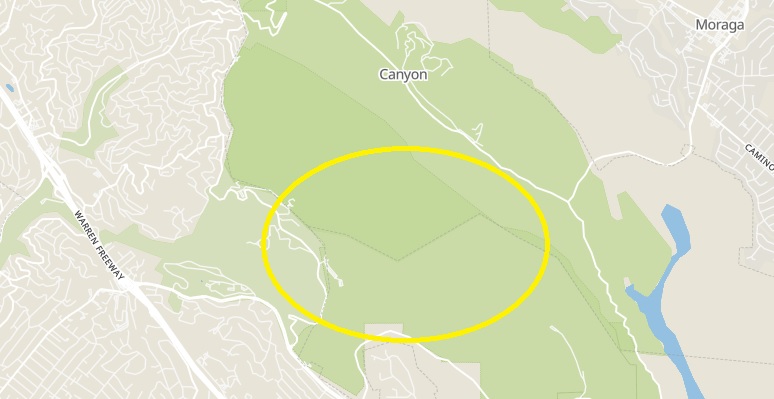

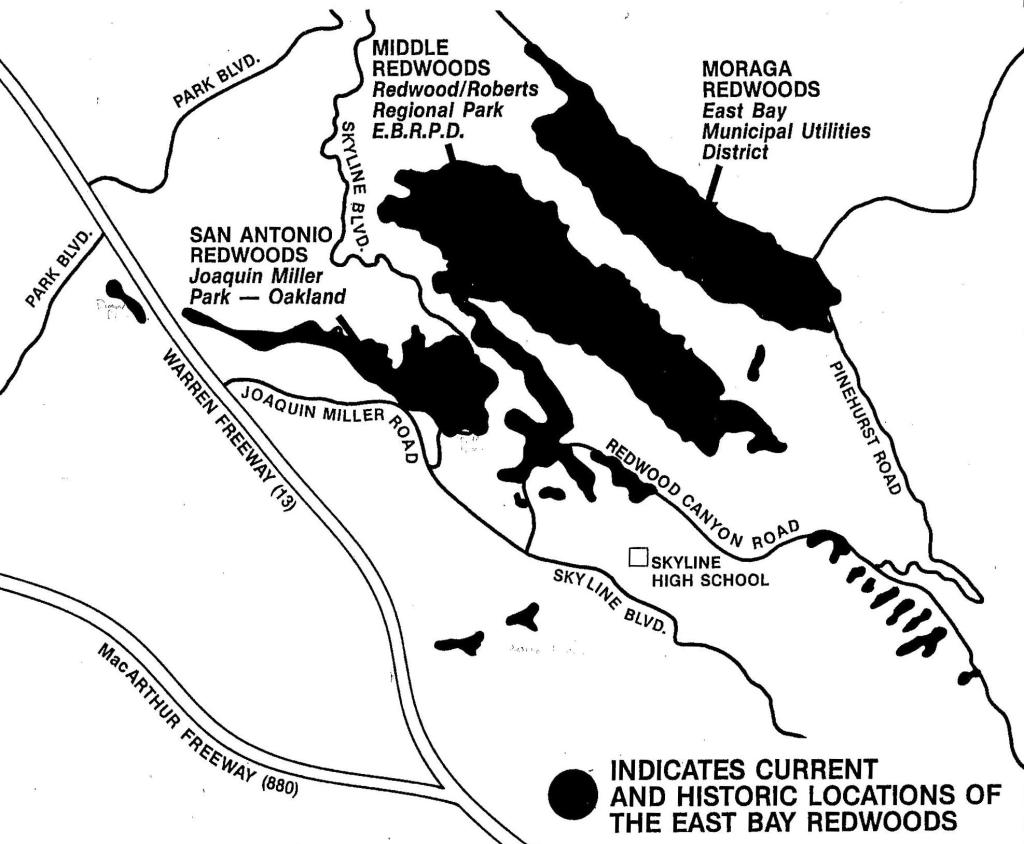

The sixth and last “island” of virgin redwoods was a tiny speck compared to the other five. Covering about 5 square miles or 3,000 acres (coincidentally, about the same size as the virgin stand in the Headwaters forest) this stand began in the westward-facing valleys of Palo Seco Creek and Leona Creek in the Oakland hills, covered a mile or so of the skyline, filled the valley that is now the heart of Redwood Regional Park plus a few small groves in upper Chabot Regional Park, and jumped over a ridge to fill the northeast-facing slopes of the valley of upper San Leandro Creek from just above the town of Canyon to just below the intersection of Pinehurst and Canyon Road out towards Moraga. On some early Spanish maps this stand was called “Palos Colorados” (“Ruddy Timber”). Along with fully 96% of all the 2-million acres of all the virgin redwoods in California, 99.999% of the original Palos Colorados are now gone, first cut as early as the 1830s by European nationals, then logged off in earnest by Americans from about 1846 to 1860.

The 0.001% is a solitary virgin tree in Leona Heights Park in Oakland. To see it, drive up Redwood Road and turn right on Campus Drive towards Merritt College. Turn left into the parking lot of Carl Munk Elementary School. There an inscribed boulder (with a young cedar inexplicably planted in front of it) placed in 1981 by the Daughters of the American Revolution points the way, across the valley, to the “Old Survivor.” It’s grizzly, shaggy, misshapen, unbalanced, not a tree that ever thrived. It survives precisely because it’s perched precariously on a steep, rocky slope, because it has had a hard life and so is not very big for its age (currently about 440 years, based on a 1969 core ring count). It would be a poor specimen in even a poor stand of most virgin redwoods.

Yet these very hardships are what rendered Old Survivor unsuitable for logging–and what spared it. As with the Chinese under Mao, sometimes it pays to be poor. It’s possible to clamber to the tree, but only if you’re thoroughly immune to poison oak and have a John Muiresque disregard for life and limb. The views from the school or from the fire road above it are better anyway, clearly contrasting the Old Survivor’s dark, heavy form with the light, upward sweep of the surrounding second growth.

Along with the Jack London Oak in front of City Hall, and the 64 palms on Ninth Ave., Old Survivor has the honor of being a City of Oakland Landmark Tree. It’s certainly the oldest tree in Oakland and probably for quite some distance around, dating back to the time of Elizabeth I and the middle of the Ming Dynasty in China. It already stood when Sir Francis Drake became the first European to land somewhere around here, and two centuries later when the early Spanish expeditions became the first to map and name the Palos Colorados. It stood while Junípero Serra’s missions were planted and when they declined, while the Californios enjoyed their brief season of glory, through the Bear Flag Republic, the Gold Rush, statehood, the arrival of the Transcontinental Railroad, the coming of cars, through two World Wars, and the building out of the eastshore cities. It has survived three recorded major earthquakes and who knows how many unrecorded ones. And it still stands, our one witness to the time before our time, our one and only truly ancient local denizen who was alive before all that happened to bring about California and the Bay Area as we know it had begun.

The remaining trees of the forests will be so few that a child could write them down.

Isaiah

Since the Palos Colorados comprised less than 0.2% of the original California redwood forests, there would seem to be no special reason to lament its demise, other than an Oaklander’s sadness over having lost a world-class natural treasure in what was to become our own back yard. But one Dr. William P. Gibbons has given us a further reason to specially lament the loss of the Palos Colorados. Gibbons, an Alameda medical doctor and co-founder of the California Academy of Science, first visited the Oakland Hills as a youth in 1855, when most of the virgin trees were already gone. What he saw haunted him his whole life. In an 1893 article in the inaugural volume of the journal Erythea, then the organ of the U. C. Berkeley Botany Department, edited by Willis Linn Jepson, Gibbons dolefully reported the results of his post-mortem on the forest. What is astonishing is his measurements of the larger stumps he found: many from 12 to 22 feet in diameter, one fully 30 feet without bark (nearly the cross-section of the Campanile), and a prodigious triple-trunk that had merged to yield 57 feet of solid wood. None of these stumps survives today and their exact locations are lost.

No coast redwood measured elsewhere has exceeded 26 feet in diameter. So what gives? Were these uniquely titanic specimens of an already giant race? Or was Gibbons one to overstate his data? It’s impossible to know. Erythea was a thoroughly scientific journal. Gibbons reported taking many reputable fellow observers (including Muir and LeConte) on numerous outings to the stumps. So, it’s not easy to posit gross exaggeration. It is much warmer here than up north, and there’s more sunlight. However, the Oakland hills are much drier than places where the largest redwood grow today, so it’s hard to imagine specially vigorous growth here for a very thirsty species. This is one of the mysteries–and one of the heartaches–left for us to ponder.

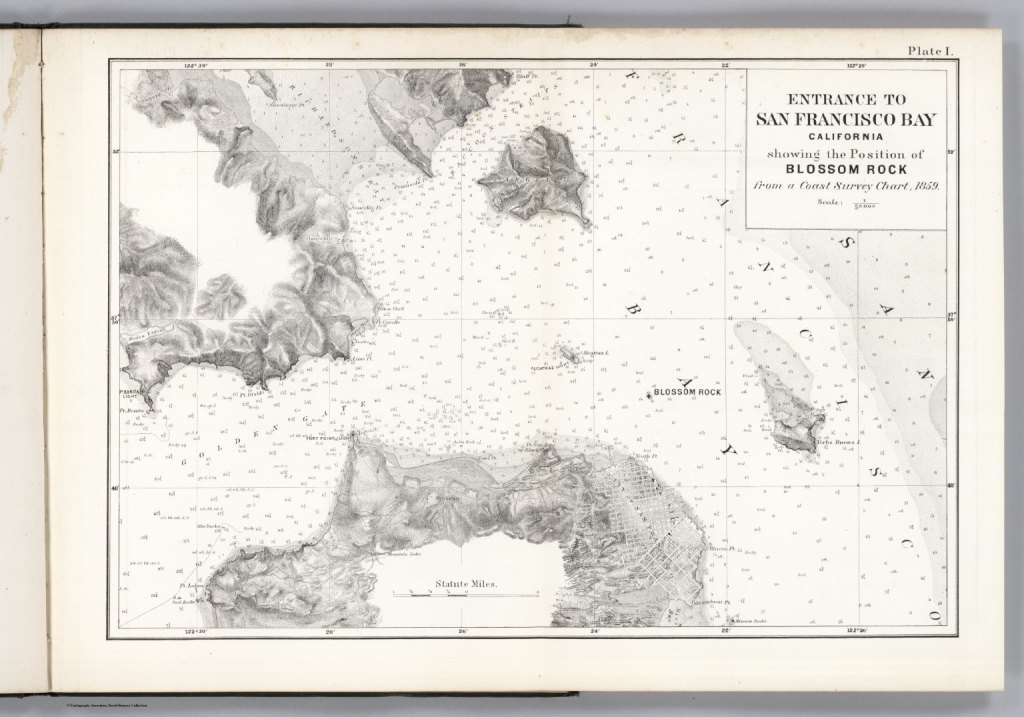

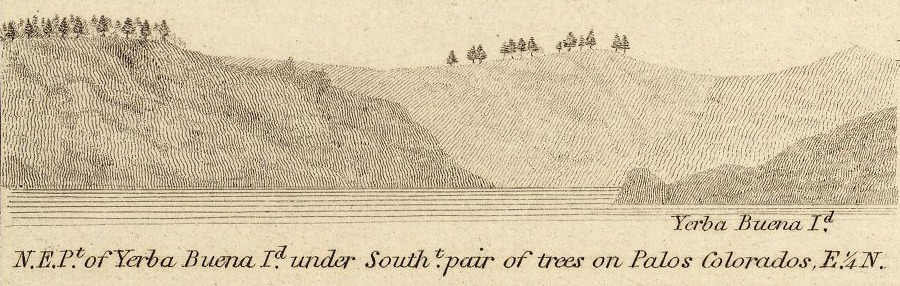

One other indication of the unique size of the Palos Colorados trees is a navigational aid described by Captain Frederick William Beechey of the Royal Navy. From 1825 to 1828, Beechey sailed the Blossom on an epic voyage from England, across the Atlantic, around Cape Horn, up to California, on to the Bering Strait, down to Hawai’i/Sandwich Islands, and all the way back to England. While in our Bay, his crew discovered a treacherous submerged rock between Alcatraz and Yerba Buena islands, and named it after their ship. To locate it when entering the Golden Gate, he wrote that one should line up the northern tip of Yerba Buena island “with two trees (nearly the last of the straggling ones) south of Palos Colorados, a wood of pines situated on top of the hill, over San Antonio, too conspicuous to be overlooked.” Imagine, too conspicuous to overlook at a distance of some sixteen miles. What trees they must have been! What trees!

The probable location of the Blossom Rock Landmark Trees is now California Registered Historical Site #962, near the bottom of the picnic sites outside the entrance of Roberts Recreational Area. An interpretive display there suggests that these trees were actually a gigantic double-stem specimen that was the very 30-foot diameter tree at which Dr. Gibbons and his scientist friends picnicked. In 1870, 4,300 pounds of explosives were used to reduce Blossom Rock to a safe depth. But not before the Landmark Trees were gone, trees whose stupendous size and peerless location made them unique in all the world. Second- and third-growth trees (including two about 24 feet apart on the probable site) again fill out the most southerly redwoods on the skyline, now rather fully instead of “straggling.” It’s impossible to know how many ships the Landmark Trees saved from harm. If only they could have saved themselves.

I love big, old trees. They humble and inspire me, having survived and thrived for so much longer than my life, so very much longer than any of my problems. Like Gothic cathedrals and old-world cities, old trees humble the individual because they exist on a time-scale far greater than any individual. For America, ancient forests and other natural wonders were also the splendid consolations of a continent that had no Coliseum, no Versailles, no Vatican, no castles, no pyramids, no Great Wall. Big, old trees are our living connection to the distant past and a towering presence in the here and now. John Steinbeck called redwoods “ambassadors from another age.” Among trees are found by far the largest as well as by far the oldest life forms on earth. They are the true giants, the sentinels, the ancient ones, the natives of the land. The rest of us are merely passing through. Each one takes root in one solitary spot, and there makes it stand, day and night, rain and shine, while animals, birds, and smaller plants come and go. They inhabit a splendid world quite beyond the realm of human accomplishment or ability. Spend some hundreds of millions of bucks and you can erect a world-class church, museum, stadium, or office tower in just a few years. But no amount of money can create a great tree in place. It takes sunlight, rain, air, the divine spark of life, and far more time than any one of us has been given in this life.

And California is arborally blessed. Garcí Ordóñez de Montalvo’s otherwise forgettable chivalric fantasy Las sergas de Esplandián (1498) imagined our eponymous Queen Califía and her she-race of Amazonian giants joining in a siege of Constantinople. As it turned out there were giants in the land: trees. Indeed, California is graced with the tallest measured tree (tree Hyperion in Redwood National Park, measured in 2006 at 380.1 feet, surpassing the National Geographic Tree in Tall Trees Grove, Redwood National Park, at 367.8 ft. in 1964; and the now recumbent Dyerville Giant measures some 370 ft.), the most massive tree (a sierra redwood at c. 6,167 tons: the General Sherman Tree in Sequoia National Park), and the oldest living tree (a bristlecone pine at 4,700+ years: the Methuselah Tree in the Schulman Grove of Inyo National Forest above Death Valley). That makes them the tallest, most massive, and oldest living things on earth.

History and legend tell of great trees in the past: the mighty cedars of Lebanon, supplying timbers to Solomon’s Temple; the aboriginal pine forests of the American strand, so verdant that their scent could be detected by the seafaring colonists at some 60 leagues (180 nautical miles) and growing so densely it was said a squirrel could scamper from the Atlantic to the Mississippi and never touch the ground; the enchanted cedar forest where Gilgamesh and his pal Enkidu battled the evil Humbaba. But the real and living great trees live here, in our State; or, should we say, we live here in theirs.

The cedars in the garden of God could not rival it, nor could the pine trees equal its boughs, nor could the plane trees compare with its branches– no tree in the garden of God could match its beauty.

Ezekiel

Redwoods belong to the (regrettably unpicturesquely named) swamp cypress family (Taxodiaceae) of conifers (Conferale). Of the ten genera of Taxodiaceae, six have only one species each, depending on how one counts–there are always proposals for recognizing new species based on all manner of variations found in specimens. Of these monotypic genera, two are native to California (Sequoia, “coast redwood”; Sequoiadendron, “sierra redwood” or “giant sequoia”), two to China (Metasequoia, “dawn redwood”; Glyptostrobus, “Chinese swamp cypress”), and two to Japan (Cryptomeria, “Japanese cedar”; Sciadoptitys, “umbrella pine”)–a bit of tidy Pacific-Rim symmetry. Three are commonly known as “redwoods”: the dawn, sierra, and coast redwoods. In a convenient bit of official ambiguity our State Tree is the “California Redwood,” so that it can be taken as the coast or the sierra redwood, or both.

Fossil redwoods including numerous extinct species can be found in huge swaths across North America, Europe, and parts of Asia. But living stands of native coast redwoods are only found on the northern California coast and a bit of southern Oregon; sierra redwoods only in about 75 isolated groves in the western Sierra (the smallest grove having only mature six trees, some 50 miles from the next closest grove!); and dawn redwoods only in one remote set of valleys on the border between Sichuan and Hubei Provinces in China. Climactic changes had pushed all three species to the edge of extinction long before steel axes and steam engines came along to hasten the process. Some of what get sold at your local gas station was probably once redwoods of one kind or another. We drive along and send their remains out our tailpipes. Trees now living absorb the carbon dioxide residue of their ancient ancestors, finally completing one turn of the carbon cycle.

While all three species of redwood nevertheless continue to grow and reproduce vigorously in their native ranges and all three have been widely planted around the world, their virgin, old-growth stands have suffered heavy losses to logging. The native stands of dawn redwoods are in areas settled by humans only in the past three or so centuries. They were being consumed by locals for firewood and construction when Chinese and American scientists identified the species in the 1940’s (before then it was thought to be long extinct) and launched a successful campaign to preserve the remaining stands.

The sierra redwoods were mercilessly cut in the late 19th-century before the poor quality of their wood for lumber was conceded. Now perhaps 70% of their virgin growth remains, 68% protected in parks and national forests.

But the coast redwood has been far too tempting for far too many: an immensely useful and workable wood, straight-grained, lustrous, especially durable, readily accessible, and available in gigantic quantities. “As timber the Redwood is too good to live” complained John Muir, bitterly. In a little over a century and a half, all but 4% of the virgin stands were cut. Of that 4%, well under 1/2% remains in private hands. That smallest fraction of original old growth is what all the fighting has been about: Earth First!, the Redwood Summer of 1990, Charles Hurwitz, Maxxam, Pacific Lumber, Judi Bari, Woody Harrelson, Butterfly’s Tree Luna, Forests Forever, and all the rest.

But the fight came far too late for the Palos Colorados. They were gone before the Sempirvirens Fund, Sierra Club or Save-the-Redwoods League, before photography, before state or national parks, before anyone knew just how thinly our beneficence of forest stretched, how quickly it could disappear, or how much its loss would be lamented.

It’s all but impossible to imagine several hundred loggers speaking a handful of European languages roaming the Oakland hills, felling the giant trees, blasting and sawing them to pieces, hauling them with oxen out and down to the waterfront, haggling over their price, all only a century and a half ago. I get dismayed just thinking about the sheer physical effort it took. But, then, life could be lived with pretty low overhead then, especially for squatters who paid little or nothing for the trees they took. Some paid $1.25 an acre to the State, but most paid no rent, fees, taxes, workman’s comp., or health insurance. It was just cash for lumber off someone else’s land.

Those someone elses were Antonio Peralta, Joaquín Moraga, and the public (under Mexican and then American rule), who held the San Antonio, Moraga, and middle sections of the redwoods respectively. Before them were the Ohlones. Before them were only the grizzly bears, mountain lions, condors, and eagles. In our moral accounting, we Americans didn’t think it right that a few Californios should enjoy the good life on immense, mostly undeveloped pieces of land. Land is to be used: logged, cleared, ranched, farmed, subdivided, sold, paved–whatever. It couldn’t just be. It was immoral for profit not to be taken, at least, more immoral than for someone else’s land to be taken. To Get Rich Quick is an American birthright, our Manifest Destiny. In the words of journalist John O’Sullivan, who coined that phrase in 1845, we Americans sought “the fulfillment of our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our multiplying millions.”

Meaning: if no one else was making bucks off this land, then, by God, we would, and lots of us. And so we did. We exercised our startling capacity to alter the landscape, to think nothing of cutting down a forest (with Paul Bunyan our folk hero), or to wash away hillsides looking for gold, or to fill in marshlands, or to send rivers flowing hither and yon. We didn’t overspread the continent and change it because it was ours; we made it ours by overspreading and changing it.

They will chop down her forest, dense though it be. They are more numerous than locusts, they cannot be counted.

Jeremiah

Even beyond their economic value, these trees were doomed by their irresistibility, as if daring men with axes to see if they were a match for felling a giant. A great mountain satisfies the ego in being climbed, a great ocean in being crossed. But a great tree can only be cut. To admire and to preserve are exercises in humility and restraint–qualities not abundant in the American pioneer spirit. And what could the trees do in their own defense? Unlike the grizzly bears and mountain lions, the trees could not even flinch. They stood in place and silently waited their demise. Their very bark and wood were soft and yielding in all their immensity, rewarding each axe blow generously. (It wasn’t until after the Civil War that steelmaking developments made long crosscut saws possible.) And so the forest fell, reduced to innumerable planks, posts, grapestakes, shingles, and mounds of waste.

Small-scale logging by Irish, English, and French ship deserters had begun by 1840, but the market was uneven, with low-cost redwood lumber coming from large operations in the Santa Cruz area. Americans arrived in 1846 and began felling trees in the San Antonio portion of the forest (the westward facing slopes now in Oakland city parks) and finishing the lumber by hand. The Gold Rush both suspended lumbering briefly and created the boom towns that sent the price of lumber skyrocketing ten- and twenty-fold. The first local steam mills were built in 1849: the Palo Seco Mill near the present intersection of Park and Mountain Boulevards, and the Taylor and Owens Mill in the Moraga redwoods somewhere near the present-day community of Canyon. By 1854, four others had been built in the middle redwoods (now Redwood Regional Park) and acreage claimed through devices ranging from outright squatting, claim jumping, dubious financing and real estate deals between mill owners, and the State’s cash-raising sell-off of land designated for schools.

The Peraltas complained but ultimately found their Mexican land titles no match for the East Coast entrepreneurs with visions of subdivided townships; their lawyers; the General Land Office, overwhelmed with irregular, exaggerated, and bogus claims; the swarms of disappointed gold-seekers convinced that unsettled land was theirs for the taking and selling; and the lumbermen who were busy making capital of the redwoods just as quickly as they possibly could. The Peraltas had long allowed their neighbors to take trees freely for non-commercial use. (Their earliest known construction use was for the main timbers of Mission San José at the beginning of the 19th century.) But their new neighbors would not be satisfied with less than all the trees, and the land as well–everything that could be had. We took this grand beneficence of trees and we made the greatest possible profit from them as early and as quickly as we possibly could.

When Alameda County was formed in 1853, its boundary with Contra Costa County was drawn with a very careful jog dividing the redwoods cleanly in half. By then there were upwards of 450 men lumbermen who needed to be divided into equitable voting precincts. But the need didn’t last long. The Contra Costa County redwood precinct was abolished in 1857, and the Alameda County one in 1860.

For by then only a sea of stumps remained in the San Antonio, middle, and Moraga redwoods that had made up the Palos Colorados. In just over a decade, nine steam mills were built and operated until they either accidentally burned down or ran out of trees to cut. It was long thought that not a single virgin tree had been spared, until Old Survivor was discovered in 1969 by Oakland Park Naturalist Paul Covel in what was then McCrea Memorial Park.

Arborgenocide. Dendroholocaust. The first clearcut of an entire virgin forest in California. The destruction of a whole population, not for reasons of hatred, only reasons of gain and greed. When a forest suffers so, whose loss is it? Wherein is the offence? Who is there to forgive? Who can do the forgiving?

By your messengers you have heaped insults on the Lord. And you have said, “With my many chariots I have ascended the heights of the mountains, the utmost heights of Lebanon. I have cut down its tallest cedars, the choicest of its pines. I have reached its remotest heights, the finest of its forests.”

Isaiah

Most of the mill owners went on to serve as State legislators, county supervisors, or leading businessmen. The lumberjacks and mill workers melted back into the populace, some perhaps moving to work the vast stands of redwoods to the north. While in our hills, these workers had gained a reputation as the “notorious mob element from the redwoods.” More than a few times these “redwood boys” lynched a cattle rustler or two. Once, fully 250 of them, armed, marched into Oakland to extract an accused rustler, threatening the mayor with burning down the town. (The mayor–the ever-practical Horace Carpentier–appeased them with a promise to use city funds make good the losses, since the accused was the city pound keeper who had used his offices to abscond with the cattle.) Their handling of the ox teams that hauled out the logs was often brutally unskilled and cruel, with the report of rawhide whips cracking through the forest.

From the Ain’t Nothing New file comes this diary entry from one Joseph Jameson (sometimes cited as “Lamson”) from Maine, who stayed in the Oakland hills in 1854. Substitute “car” or “television” for the livestock and see how it reads.

August 17, 1854. My neighbor, Mr. R., has lost an ox. It was stolen; and a horse stolen also. Another neighbor, Mr. A., has lost three valuable oxen in the same way. . . . [there are] too many inducements to the numerous idlers and vagabonds that prowl about the land to be visited; and consequently theft, robbery, and I may almost add, murder are but every day occurrences. No man who owns a horse, or an ox, or swine, can feel secure of them for a moment when out of sight.

Of course, a good number of those livestock had been stolen from the Californios in the first place. It was the wild, wild west, set in a redwood forest. Only, in the end, the forest itself was driven out of town.

Are the trees of the field people, that you should besiege them?

Deuteronomy

And there is no turning back the clock. Of course I would bring the trees back if I could but to do so might preclude my own life. So many of the advantages I’ve enjoyed–a first-world standard of living, access to world-class education, and work that is so greatly removed from any worry of day-to-day survival–are possible only because of the wealth that has been created on this land. (My ancestors didn’t come here for the natural wonders.) In just a few generations after the Gold Rush, European and American settlers and an assortment of migrants of color had prospered here and built the growing new towns and cities that became a destination of hope for my grandparents, an eagerly embraced alternative to the chaos, crowding, and poverty of southern China early this century. Here, met by exploitation, indifference, curiosity, hatred, opportunity, and kindness, they lived out their wholly transplanted lives. Here they set into motion the events that led to my own life here, a life that is surely blessed even far beyond the hopes they brought to these shores. Without the wealth that was created on this land, I would not be here, and not be near these trees both living and gone that so inspire me.

So I cannot fully begrudge the settlers who took and changed this land. Yes, they could have been more respectful of the Ohlones and the Californios, less bent on their Get Rich Quick schemes, and earlier to recognize the enduring value of unspoiled natural wonders for coming generations. But many of them had to worry about survival–about having food to eat and a place to live–in ways I’ve never had to. Contemplating big trees is pretty high on Maslow’s pyramid of needs. Perhaps I’m the one who needs to be forgiven, for taking for granted the debt I owe them for their choices and efforts, from which I benefit so greatly. And for standing in some untracable line of benefit, however long and indirect, to the cash and construction value of the trees that once were here.

As far as I can tell, there are only two contemporary images of the Palos Colorados as it stood, neither very satisfying. The first is a sketch in the corner of Captain Beechy’s 1827/28 map of the Bay, detailing the visual markers for avoiding Blossom Rock. It shows an islolated tuft of trees south of the main grove, and then two solitary specimens still farther south. These southernmost “landmark trees” are clearly separate trees (not a twin-trunked individual) and are depictced about the same height as those in the tuft and in the main grove.

The second image is the Oakland Museum’s 1853 six-plate panoramic daguerreotype of that other city (the one with the naturally deep harbor, whose periodic conflagrations fueled so much of the local market for lumber), the fifth plate of which has the Oakland hills in the background, on top of which are the faintest wisps of a very thinly forested skyline. It almost looks like a flaw on the plate; but the daguerreotype technique is given to extraordinary detail rather than flaws. So that may be the best image we have of our forest as it once stood.

Nevertheless, in a very real sense, many of the fallen giants do live on and can be seen and touched, even after their mighty boles had been cut down, blown apart, and sawn into millions of pieces. The giants live on because coast redwoods are capable of root crown sprouting: the ability to send up new shoots from even a fragment of peripheral stump. No other conifer does this. Cut down a sierra redwood and all you will have is a mighty stump to weather and age for the next few centuries. But cut down a coast redwood and new sprouts emerge and grow into trees. Since some part of the original root system may be used by the new growth, this isn’t quite cloning. It’s also not reincarnation or resurrection, which require something to fully die first. It’s more like morphing, or rather, regenerating. So the species is named sempervirens, ever-living.

The second- and third-growth trees that make up the redwood forest in our hills are largely former root-crown sprouts, with a small fraction of seed-grown trees and a very small number of planted specimens (the largest number of which were sponsored earlier last decade by HealthNet and Save-the-Redwoods League in an effort to replace eucalyptus being removed from Joaquin Miller Park). The titans were felled but they wern’t killed. Everything that once made them titans remains to make them titans again. Indeed, this cycle of demise and rebirth had been going on for eons before the axemen and millwrights arrived, albeit tree by tree over the centuries rather than the whole forest in a score of years. Without this capacity to regenerate, we would have no redwood forests at all in our hills today.

If the great stumps remained in the hills, at least they would still bear witness to what was lost. Alas, very few stumps remain. Dr. Gibbons reported that even the stumps were ravaged, broken up for firewood, much of it, it’s thought, by Chinese immigrants. He reported that one grubber bragged of taking fully seven cords of four-foot wood from a single stump. That would make a woodpile eight feet tall and twenty-eight feet long. (As a not-very-dense softwood, redwood burns fast and not very hot, making it a second- to third-rate firewood.) Again, my mind reels at the effort it must have taken, chopping out the wood, hauling it out, haggling over its price. Undoubtedly some of this wood fed the boilers of the steam mills, like boiling a kid in its mother’s milk. The remains of one large stump are across from the entrance of the Archery Range. In 1971, Oakland Park ranger Louis O’Dell reported finding the remains of another stump, also near the Archery Range, with progeny from sprouts almost 33 apart–perhaps Dr. Gibbon’s mighty stump.

Wail, O pine tree, for the cedar has fallen; the stately trees are ruined! Wail, oaks of Bashan; the dense forest has been cut down!

Zechariah

Given enough time, the steep, forested creek bottoms of the Oakland hills will erode away, leaving only rolling hills too exposed to maintain the damp conditions redwoods require. Even in the few years I’ve run regularly through the woods, I’ve seen countless bay laurels toppled, slides and wash-outs, and deepening erosion channels. Indeed, so much of the East Bay flatlands where most of us live is alluvial deposits, washed down from our hills. Given enough time, I suppose the very surface of the continents as we know them will erode into the sea. Water running from mountain to hill to plain to sea carries the land with it, grain by grain. And the raindrops always return empty handed.

Even in the short term, axes and saws are not the only enemies of forests. Lightning-caused fires wipe out tens of thousands of acres of forest every year, contributing a significant percentage of worldwide air pollution. Mount St. Helens obliterated a whole forest in less time than a logger takes to gas and oil his chainsaw.

Even our human efforts at preservation can lead to destruction. Smokey the ”Only You Can Prevent Forest Fires” Bear was created during WWII to try to safeguard timber needed for the war effort. But the practice of fighting all fires has led to two generation’s worth of flammable debris on forest floors. When a fire does strike, often from lightning, this thick, unnatural accumulation of fuel results in an explosively hot firestorm that incinerates even mature, standing trees that would have survived any number of smaller periodic fires. Without mature trees holding their ground and spacing out other growth, new trees may grow back too thickly for any to thrive, leading to another heavy accumulation of fuel. Once again, the Law of Unintended Consequences strikes, most disastrously. Our 1991 Firestorm did not reach the redwoods, but someday one will, and it could be catastrophic.

The trees have other enemies as well. Redwoods are remarkably resistant to attack by disease or insects. The very oldest specimens don’t even show any signs of senescence, and will keep growing until they are overcome by physiological (drought) or mechanical (toppling, usually by wind) forces. On display in Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park, there’s a cross-section of the oldest closely-dated redwood, all 2,200 rings. The oldest wood—two centuries old when Christ was born—is as sound as the outermost layers.

But invasive exotics are another matter. In its natural state, a terminal redwood forest community is exceptionally stable. But in our hills the trees must compete with eucalyptus (those pesky foreign tree-weeds that multiply rapidly and do better than natives, planted here by the millions in a later–and doomed–Get Rich Quick scheme in the 1910’s) and Monterey pines (the out-of-towners who put up a big spread but are ill-suited and never really fit in or do well here). Choking out seedlings and saplings are ivies (long ago escaped from backyards and now blanketing many entire slopes) and brooms (with their sickening show of gaudy yellow flowers each spring).

At the top of Dimond Canyon, south of the golf course, is a beautiful stand of redwoods, in a bowl created by the fault-bent Palo Seco creek. You can enter on a trailhead on Monterey Boulevard near the tall sign depicting the Dimond Canyon Trail. This pocket of serenity includes the only patch of native redwood sorrel (Oxalis oregana) I’ve ever seen locally. It too is succumbing to ivy. Its South African cousin, the buttercup–that ubiquitous and invasive weed–is also making inroads, in an intra-genus conquest. Worst of all, ivy climbs up the trees relentlessly. I’ve seen cottonwoods and pines smothered and killed by ivy. I have nightmares that the terminal community in our hills will someday consist of ivy, broom, and buttercup, punctuated with an occasional redwood snag overcome with vines. Maybe we’ll get lucky and the ivy will strangle the eucalyptus, which will then burn in some future conflagration and take the broom and buttercup with it.

But in the end the very species that first brought depredations to these redwoods and imported menacing flora will, it would seem, ensure that the forest will not disappear. In 1928, the Save-the-Redwoods League intervened to preserve the “Hights” around Joaquin Miller’s estate. The City of Oakland eventually acquired it to help assemble today’s 425-acre Joaquin Miller Park. That park, upper Dimond Park, and Leona Heights Park include most of the former San Antonio stand. In 1939 the 1,494 acres that would become the bulk of Redwood Regional Park were acquired from the East Bay Municipal Water District by the still-new (and still breathtakingly foresightful) East Bay Regional Park District, for $246,277. That preserved the former middle stand. (In 1997, Oakland purchased an adjacent 21 acres from a developer for $3.75-million in order to protect a sensitive part of the Redwood Creek watershed.) The former Moraga stand is now mostly EBMUD watershed lands extending south and west from the the town of Canyon, between Pinehurst Road and Redwood Regional Park. Thus, the former Palos Colorados in substantially all its original range is free to continue regenerating a forgiveness forest. Somehow, we found it in ourselves to not turn it into housing, highways, farms, or even rangeland.

On a national scale, redwoods have occasioned titanic efforts aimed at their preservation. In 1968, against powerful opposition, President Johnson signed the first Redwood National Park Act. It was the most expensive land purchase by the U.S. Government in history, bar none: 28,101 acres for $198-million (in 1968 dollars). By 1978, clearcutting around the original purchase was causing so much damage from downstream erosion that an additional 48,000 acres of mostly cut-over lands was added by the Carter administration at a new record outlay of $359-million. (This second Act was surely a case of logging companies having their cake and eating it too, since most of the cutting on the purchased land had taken place in the intervening decade.) To this day, the American taxpayer is spending large amounts of National Park Service money to push dirt around in Redwood National Park and replant the badly scarred slopes above Redwood Creek.

Perhaps that shows the best and the worst of Americans: the genius for private wealth, the utter disregard for the land; the ability and desire of the people and their government to nevertheless restore and protect the land at so great an expense; the idiocy of having let the whole sad story unfold in the first place, just so a few more tracts of suburban homes could have their redwood decks on which to spill barbeque sauce for a couple of decades.

And now we’ve redeemed the last great stand of unprotected virgin trees by spending another $480-million for 10,000 acres that include the Headwaters stand. This was the last great fight for old growth redwoods. There is nothing else left to fight over. Some small, scattered virgin stands remain on timber company lands, to be cut in the next few years. Small groves and individual old-growth trees on land owned by private citizens and non-timber groups are now scouted, sold and cut. (A single virgin tree can be worth up to $100,000.) Existing parks still urgently need enlargement to protect their full watersheds. Plenty of second-growth land remains to be preserved if we’re so inclined. But in the end, between 81,000 and 84,000 acres of old growth will have been preserved, about twice the area of Oakland. In the end, about 10% of the original redwood lands, cut and uncut, will have been set aside for posterity, including those in the hills above our homes.

In my native boosterism I revel in the daydream that the world-famous Oakland Redwoods are still standing, far greater than Muir Woods, perhaps even including the World Champion Redwood. I daydream that as a cable car mounts the crest of one of those overbuilt hills across the bay, the knowing tourist could look east and see the mightiest sylvan skyline of any city in the world. What a treasure that could have been! If we in the East Bay were not to have the man-made monuments borne of world-class financial wealth, we could have had monuments of nature even more stunning.

Someday, perhaps we again will. For now we have our forests of memory, of contention, of preservation. We agonize over who benefits and who loses over the fate of trees we did not create and did not grow. And if so inclined, we lament what was once in the hills overlooking what became our home.

I’m thankful I wasn’t born a century earlier, when the slopes above my city Oakland were still denuded and the ugly scars of clearcutting were still open and bleeding. I envy those who will come of age here two and three centuries from now, for they will once again have an ancient forest by which to contemplate their lives.

That is, baring some cataclysmic environmental disaster or societal collapse that leaves the trees vulnerable again. It’s only been one and a half centuries since the forest began falling. What will life be like a hundred years from now? Two? Five? Another millennium? Some of these same trees could still be standing then. But by then, who knows if our civilization will have fallen in its turn and another taken its place. Perhaps some distant descendent of mine will write this very same essay in another century, after a new era of war, pestilence, migration, and resettlement takes its toll on these trees. Another season of offence; another occasion for forgiveness.

Meanwhile, the trees reach for the sky, drink up each year’s rain, endure each year’s summer drought, crowd and push against each other, teeter and fall when they lose their balance, and sprout and send up new growth. The forest forgives. God, who made the forest, forgives. And I am learning to forgive.

On each side of the river stood the tree of life . . . . And the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations.

Revelation

A version of this essay appeared in Oakland’s Neighborhoods, ed. Erika Mailman (Oakland: Mailman Press, 2005)

A short adaptation of this essay appeared in The Monthly, Dec, 2014